If you’re an aspiring game developer or any other type of artist, you probably recognize that your creations are valuable to you. It’s your intellectual property!

You have probably thought about protecting your ideas, and are wondering how to do that. While an idea on its own is fairly useless, you’ve worked hard on your game or other creation and the last thing that you want is for someone to come along and rip off your hard work. Creating a game, a song, a book, a video, or any other art takes a lot of work, but once it’s created it doesn’t take much time or effort to create a new copy. On the other hand, maybe you’re worried about accidentally infringing on someone else’s ideas and facing legal troubles.

All of these concerns are in the field of intellectual property, or IP. IP is especially important for the video game industry, so it’s important for a developer to understand the basics. While this post is primarily focused on game developers, other types of art are also protected by intellectual property laws.

Owning Ideas– The Essence of Intellectual Property Law

Intellectual Property (IP) is defined by the World Intellectual Property Organization as “creations of the mind[…] use in commerce.” It’s things that you can create, like art, a movie, a song, a video game, or anything else that you can create and then profit off of. It’s not the physical thing, but the exclusive right to the creation itself.

Intellectual Property is distinct from ownership of real property (like land) or personal property (belongings or things) – it is the ownership of creative works, or thoughts and ideas in a way. Intellectual Property refers to the branch of law that protects creative works.

A game or any other creative work takes a great deal of money, time, and effort to create. In every release, there are dozens to hundreds of talented people working in a variety of disciplines to create a single finished product. However, once the game has been created, it costs significantly less to produce a single additional copy.

This is the case for nearly all reproducible creative works like films, music, books, digital art, and more. IP is based on the idea that people who make creative works should be allowed to profit from their work, so it seeks to protect them from other people who would exploit that work without creating it on their own. While the underlying creative work is scarce, the actual product is not. As budgets for games get larger and larger, it is becoming even more important to protect the investment being made when creating a game.

Intellectual property comes in a variety of forms, each protecting a different aspect of a work or the business surrounding it. Here we’ll take a quick look at each one. This is not meant to be a comprehensive guide on the different areas of intellectual property, but a broad overview from the lens of game development so you can understand other issues that may arise as time goes on.

What “Ownership” of Intellectual Property Means

Owning intellectual property is not what grants you the right to create something, or even the right to produce more copies of that thing. It is instead better thought of as the right to exclude others from doing things with your work. When you own the copyright over a creative work, you have the exclusive right to make copies and you can exclude others from doing so. You also have the right to exclude other people from doing things without your permission like producing derivative works based on your intellectual property such sequels or spinoffs if you hold the copyright. You can grant permission to someone to use your work in one or more of these ways by granting a license or even transferring intellectual property outright.

With that understanding, let’s take a quick look at each of the major types of intellectual property to understand what can be protected.

Copyright

Copyright law grants protection to “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression.”1 Copyright protection extends to literary works, musical works, dramatic works, pantomimes, pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works, motion pictures and other audiovisual works, sound recordings, and architectural works.2 Video games fall under the category of “other audiovisual works” as well as “literary works” so they qualify for copyright protection as a whole in addition to the individual components (graphics, audio, story, and even code) that make up the game. A work becomes “fixed” when it is put into a form that is “sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than transitory duration.”3

For video games, a work can be considered “fixed” as soon as it is published or made available to the public, like when you publish on Steam, the app store, or wherever you opt to publish. Even though a video game changes every time a player plays it, a court ruled that a video game as a work is still sufficiently fixed to qualify for copyright protection,4 so a video game is protected by copyright even though it may not seem as “fixed” as other forms of art.

Copyright has changed in duration over time, but currently lasts the life of the author plus 70 years. The theory behind this was that it would give the author time to profit off of the work during their lifetime as well as their heirs after they die. However, most video games are not the work of a single person but are a multidisciplinary creation by a whole team of people. In these cases, the work can be considered a “work made for hire” and the duration of a copyright is instead 95 years from the year of its first publication or 120 years from the year of its creation, whichever comes first.5

Getting copyright protection is very easy. You have a copyright as soon as a work is fixed in a tangible medium. As soon as you make your work, you have a copyright over it. The owner of the copyright of a work is the creator of the work, though works made for hire and other types of collaborative work can change this default rule when multiple people contribute to a work. This is different from trademarks and patents, which require registration. However, it is still a very good idea to register anyway since the protections granted (as well as potential damages) are limited without registration.

Copyright registration gives a better damage calculation if someone infringes on your work, is required before litigation can begin, and is not expensive or difficult to do. A work can be registered at the same time as legal proceedings begin – like sending a cease and desist notice to an infringer – but registering earlier is recommended for a variety of reasons. While copyright is granted automatically by creating a work, registration is necessary in order to have any real legal enforcement and is neither expensive nor difficult compared to the benefits it can offer, so it is recommended. Enforcement is the responsibility of the copyright holder, and recent changes such as the copyright claims board have made it easier for smaller creators to enforce their rights against infringement.

Trademark

Trademark is different from copyright, but often gets confused with it. Trademark protects identifications of source, like brands, and is primarily governed by the Lanham Act6, which lays out the basic rules governing trademark registration, infringement, and statutory penalties for said infringement. Being able to identify who made a game not only allows customers to stay informed, but also allows a studio to build a brand over time.

Think of some of your favorite brands, or some brands that you’ve had a bad experience with. Each one of those is probably a trademark, and you likely have positive or negative feelings associated with your past experiences with these brands. Ownership of a trademark grants protection over your studio and game’s name, logo, and other assets that would be used to identify your studio. It allows the holder of the trademark to exclude others from using the trademark. Usually, a trademark is a word, name, symbol, graphic, or phrase used to identify the source of a product.

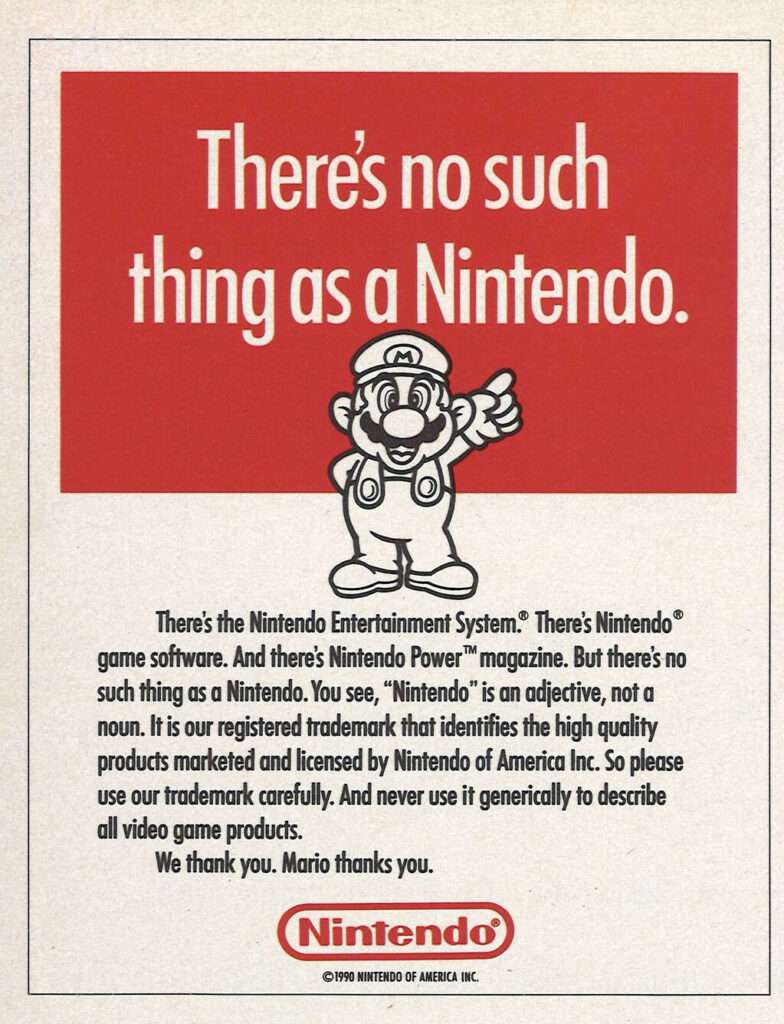

In general, a title that is used for one work only is not meant to be covered by trademark, since trademarks primarily distinguish a source of the good. However, the United States Trademark Office has made a special exception for video game titles that allows them to be protected by trademark.7 This means that “Nintendo” and “Super Mario” can be a protected trademark (a franchise is an identifier of source) as well as “Super Mario World” (a specific entry within the Super Mario franchise).

An important distinction between copyright and trademark is that failure to actively protect a trademark may lead to damage to the trademark. This is one reason why some IP owners can be particularly protective of their work against infringement by fan games.

While you may allow certain uses of your trademark by the general public, it is important to communicate with groups such as fansites what is and is not allowed, as well as what your trademark is and what works are not officially produced by your studio. If you hold a copyright, you can generally choose to enforce against some infringers while allowing others without problems.

In some cases, trademark protections can even be lost through “genericide,” where the brand name becomes a generic name for the product. Aspirin, Zipper, App Store, and Xerox are all examples of brand names that have become genericized and have had reduced trademark protection as a result. This is why Nintendo put out an advertisement in the 90s informing people that “A Nintendo” is not a generic term for a video game, as my grandma would call them, but a registered trademark. Trademark has to be policed by the holder somewhat more vigilantly than copyright.

To have a trademark, putting a ™ after a word puts people who see the designation on notice of your trademark rights when used in combination with its use in business. This is called a common law trademark, and protection begins as of its first commercial use. Registering a trademark (identified with an ®) gives additional protections. This process is a bit more difficult and expensive than a copyright registration and is usually done with an attorney or law firm that specializes in trademark registration. Unlike a copyright or patent, which has a limited term of protection, a trademark can last forever so long as it is continuously used in commerce and the relevant fees are paid throughout the term of protection. Notably, a trademark only grants protection in the areas where the trademark is in use, unlike copyright. However, when selling video games primarily through digital storefronts, this is not much of an obstacle.

When considering the name for your studio or game, a trademark search is essential. It can ensure that the trademark is not currently in use and that it can be protected. If someone else is already using the name, you won’t be able to protect with a trademark. It is much easier to change the name of a game or studio when things are early in development than when marketing is already in full swing.

Patent

Patent is one of the oldest forms of protected intellectual property, having descended from English law and having its modern roots (in the US) in the United States Constitution.8 Patents provide exclusive right to “any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter.”9 While video games don’t tend to use patents very much, as you usually can’t patent specific game mechanics – though there are some cases where mechanics have been patented – patents can be used to protect development tools, software, and other middleware. As such, they’re worth understanding at least a little bit.

Like other forms of IP, a patent is not the right to invent or create something, but the right to exclude others from doing so. When someone invents something and is able to secure a patent on it, they have the ability to exclude others from using that invention for the term of the patent.

After inventing something, you can get a patent on the invention by filing a patent registration. Patents have a relatively short term of protection compared to other types of IP, currently extending for 20 years after they are filed. After that, the public may use the invention. This is often called the quid pro quo of the patent system; in exchange for protections on the invention, the invention will later enter the public domain so everyone can build off of it and benefit from it after the inventor has had the first opportunity to profit from its creation.

In general, there is very little (but not nothing) in game development that falls into the domain of patent law. Copyright generally provides most of the protections that a game will need. For example, while the rules of a game generally cannot be patented, the specific expression of those rules, the game itself, can be.

Trade Secrets

I’ve included trade secrets here even though it’s a bit different from the other forms of intellectual property. Unlike copyright, trademark, and patent, trade secrets generally are not rights created by law, but are created by contract and company practices. There are laws that protect them, but you usually do so by doing what you can to maintain their secrecy.

A trade secret is something important to your company’s operation that you’ve taken measures to keep secret. It may be protected by non-disclosure agreements in contracts and practices to limit how many people learn of the trade secret. However, courts will have limited ability to prevent other people from using it beyond the enforcement of contracts.

Often these are the sorts of things that could be patented. Unlike a patent, trade secrets are not protected by law, so if they get out into the world, your ability to exclude others from using them is limited. However, the duration of a trade secret is only limited by how long it can be kept secret, while a patent expires and enters the public domain after a time. This can potentially allow a company to take advantage of a trade secret for far longer than a patent.

Coca-Cola is a great example of a well-protected trade secret. Coke never patented its formula but kept it a trade secret. If it had been patented, this would have required disclosure of the formula, and the public could have used it when the patent expired. While this does bear some risk of the formula getting out, ultimately keeping the formula secret has allowed them to keep it fully secret, thereby excluding others from using it, for far longer than a patent would allow. In video games the source code for a game can be a good example of a trade secret, as well as other things that are used by a developer that aren’t usually protected by other forms of intellectual property but are essential for running the studio.

Conclusion– Intellectual Property is What You Create

It is essential for a game developer to have a basic understanding of intellectual property, both to protect your own and to avoid infringing on the intellectual property of another person or company. Video games in particular are almost entirely creatures of IP, and it’s one of the most valuable assets that a studio can have.

If you are interested in how you can protect your own intellectual property, need to make sure you have the necessary rights as part of a contract, or need other legal services, contact me to set up a free consultation.

- 17 U.S. Code § 102 (a) ↩︎

- 17 U.S. Code § 102 (a)(1-8) ↩︎

- 17 U.S. Code § 101 ↩︎

- Williams Electronics, Inc. V. Arctic International, Inc. 685 F. 2d 870 (3d Cir. 1982) ↩︎

- 17 U.S. Code § 302 (c) ↩︎

- 15 U.S.C. §§ 1501 et seq. ↩︎

- Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure section 1202.08(b) ↩︎

- United States Constituiton, Article I, § 8, clause 8, granting Congress power to “promote the progress of science and the useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” ↩︎

- 35 § U.S.C. 101 ↩︎

Leave a Reply