A story was recently published by PC Gamer that caught my attention. It concerns someone copying another developer’s game, and got me thinking about the legality of cloning games, or making a direct copy of someone else’s game, recreated from scratch.

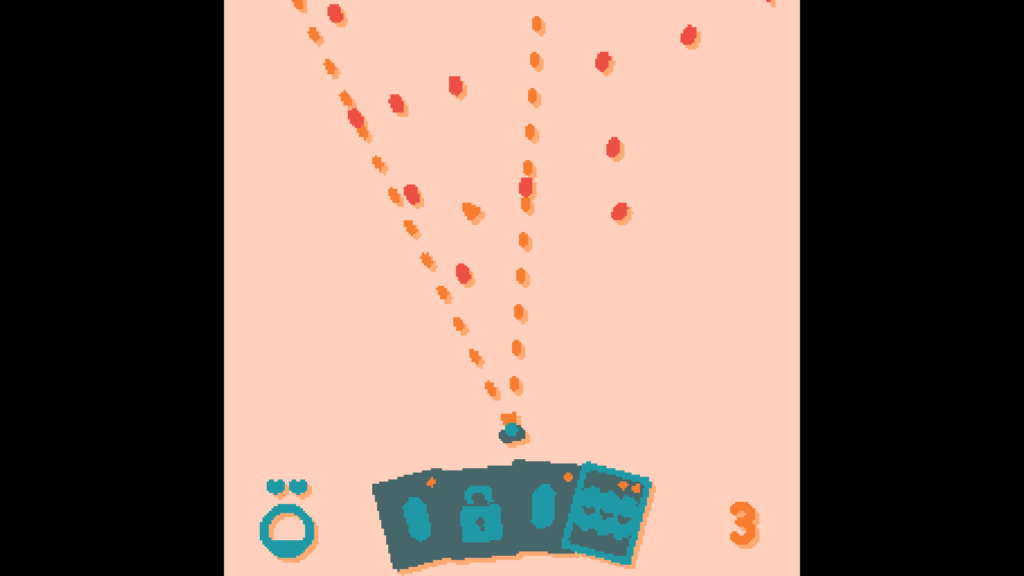

The story is about a developer by the name of Kindanice who developed a game called Dire Decks, a deck building tower defense survival game. He talked with another developer named Terry Brash. They were fans of each other’s games, and Brash invited Kindanice to his developer Discord server. A year later, Brash sent a DM to Kindanice with the news that he had cloned Dire Decks, added a few features, and put it on Steam with the name Wildcard published under his name.

Dire Decks and Wildcard are VERY similar games. They not only share the same basic concepts and game design, but Brash went so far as to copy Kindanice’s graphical style and elements to a T, UI elements, color choices, gameplay loop, as well as most of the iconography for cards. I don’t usually like to call a game a copy of another one, but if I didn’t know any better, I would assume the Wildcard was a polished-up version of Dire Decks intended for a Steam release.

When Kindanice asked if Brash thought it was okay, Brash just asked if Kindanice wanted an “inspiration” credit, saying that “I liked the game, so I made a clone with extra stuff. Happens every day homie.”

Now to be clear, something like this does happen pretty often. Developers of all sorts are often cloning games. Taking inspiration is natural in any art form, and is how we’ve had entire genres pop up. Games in the first-person shooter genre were called “Doom Clones” in its early days, and there have been a lot of games inspired by Dark Souls, to the point that an argument being made that it created a genre called Souls-likes.

But where is the line between inspiration and a shameless clone? While I can’t comment on the specifics of this situation (I’ll leave that to the developers to sort out) and I can’t draw any sort of conclusion regarding these two games and how much was cloned, let’s talk about where the line might be in terms of the law by looking at a similar case. How does the law view cloning games?

What Does Copyright Protect?

The first thing that we need to understand is what copyright actually protects. Copyright protects “original works of authorship.” If you create something, it’s protected. This can be a literary work, music, novels, movies, songs, software, or any other artistic work. Yes, courts have decided that copyright protects video games, even though the player’s interaction with them makes them unique each time they are played.

Individual assets within a game are also protected by copyright. Any clone that we’re discussing will have to create original assets to avoid infringement.

What copyright does not protect is ideas. While you can protect the particular expression of an idea, you can’t protect the idea itself. This is often called the idea-expression dichotomy. While Super Mario Bros. is protectable by copyright, the idea of a plumber platforming through a world and fighting a turtle in a castle is not.

Where the idea ends and the specific expression begins is a case specific question. The concept of a guy in overalls climbing up a metal structure to rescue his girlfriend from a large ape doesn’t get protection as far as the law is concerned, but the specific expression of that idea – the arcade game Donkey Kong – would be protectable.

The other element that copyright generally doesn’t protect is game mechanics. Those are usually the domain of patent, and even then protection of specific gameplay mechanics is very rare, but not totally impossible. There’s usually not much stopping you from taking existing mechanics and putting your own spin on them.

In video games, code is also protectable, as we touched on when discussing the legality of emulation. However, when we’re talking about cloning games, we’re not looking at cases where a developer steals the whole code of another game. That’s pretty clearly copyright infringement. What we’re looking at is someone taking someone else’s game and creating their own version of it from scratch. In other words, the legality of what they’re doing isn’t quite as clear cut.

Tetris vs Mino: What is the Legality of Cloning Games?

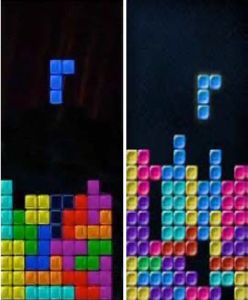

While you generally can’t protect a concept, idea, or usually gameplay mechanics, you can actually go too far when directly cloning games. Fortunately, there has been a legal case about this, where one company cloned another company’s game and there was a lawsuit that went to court. For that, we’ll take a look at the 2012 case of Tetris Holding, LLC v. Xio Interactive, Inc.

In Tetris Holding, The company that owns Tetris claimed that Xio Interactive infringed their copyright and trade-dress of Tetris. Xio created a clone of Tetris for iPhone under the name Mino, a name which itself is derived from the name for an individual block in Tetris, a tetromino. Xio admitted that they were more than a little bit inspired by Tetris and that “its game was copied from Tetris and was intended to be its version of Tetris.”

While Mino and Tetris are very similar games, similar enough that you could look at two screenshots and likely not be able to pick which one is which, the court pointed out that many of these common elements are not protectable by copyright. Blocks falling, lines, a grid, or even a box that shows a next piece are not protectable by copyright on their own.

Legal doctrines like merger and scènes à faire (a phrase meaning “a scene must be done”) protect cases where there is only one way to express a specific idea. If something is necessary to the expression of a particular concept, it can’t be argued that anybody else expressing that concept is infringing when using it. Blocks falling from above? That’s a pretty necessary element to the falling block puzzle genre, so Tetris can’t have that protected by copyright.

However, the court ruled that “this principle does not mean, and cannot mean, that any and all expression related to a game rule or game function is unprotectable. […] Tetris Holding is entitled to copyright protection for the way in which it chooses to express game rules or game play as one would be to the way in which one chooses to express an idea.”

The court determined that the two games were so similar that a layperson would not be able to distinguish them. The style, look, movement, rotation, behavior, colors, and texture of the blocks were very similar, as well as other elements like the size of the grid, the presence of ghost pieces, how garbage pieces appear, and the dimensions of the playing field throughout the game. The specific Tetris pieces were not necessary to design a puzzle game. The court ruled that many of these elements were eligible for copyright protection despite being a part of the functionality and rules of the game.

From this case, we learn that it is possible to go too far when cloning games. While it isn’t possible to protect a game’s basic mechanics and rules with copyright, a developer is allowed to protect the specific manner in which it chooses to express them.

Conclusion: Inspiration vs Copying

Was Brash wrong? Is cloning games something that “happen(s) every day”? Maybe.

While it would be irresponsible of me to draw any sort of conclusion on the specifics of Dire Decks and Wildcard, there is such a thing as going too far in the eyes of the law when cloning games.

Is it legal to clone a game? Sometimes, and you have to be careful not to copy the specific expression of the original game or else you end up in a position like Xio Interactive did with Mino.

Other court cases, such as the one from the tabletop game world between the creators of the card game Bang! and Legends of the Three Kingdoms, have shown that courts are somewhat willing to go beyond the strict interpretation of what is protectable to discourage creators of clone games, even where elements such as art and other visual assets are changed. In other words, actual mechanics may be protectable under some circumstances.

Copyright law aside, is it morally right? Game developers are artists, and I tend to think that we should be aiming to create something original without just cloning games that someone else has worked hard on for a quick buck.

In any case, if you’re inspired by something and want to create something like it, that’s great! But make sure that you go beyond shamelessly copying your inspiration and aim to innovate, expand upon, and go in a new direction with what inspires you.