On March 4, 2024, Tropic Haze LLC, the creators of the Yuzu Switch video game emulator, announced that they would be ceasing development and stopping distribution. This was the result of a lawsuit by Nintendo, which Yuzu’s development team ultimately settled for $2.4 million.

Incidentally, this happened not long after Dolphin, a Gamecube emulator, canceled its planned Steam release after Valve’s legal department contacted Nintendo about their plans.

So what did Yuzu do wrong? Is Nintendo’s legal department coming for every other emulator? Hasn’t Nintendo heard that emulation is legal? We’re going to dive into that today because the law surrounding emulation isn’t completely settled – and it’s occasionally weird what is and is not legal. From there we’ll be able to better understand Yuzu’s situation.

What is a Video Game Emulator?

In order to discuss the legality of emulators, we first have to discuss what an emulator is.

In the video game context, an emulator is a program that imitates – or emulates – a console or other hardware. Typically this allows you to play games (or other programs) on hardware they are not built for. Dolphin allows you to play Gamecube and Wii games on your PC, and Yuzu does the same for Switch games.

I’ve best explained it to people who aren’t as tech or video game savvy as a program that pretends it’s a video game console.

Emulators work by using ROMs. The emulator itself generally doesn’t include any games, it just acts like the hardware. A ROM (short for Read Only Memory) is a file that acts like the cartridge or CD you’d put into your console to play a game. It is a dump of the contents of a real game that the emulator reads to play the game.

The common school of thought outside of legally-minded people is that emulation is legal, but ROMs are not when you download them from the internet. Some people even erroneously believe that ROMs are legal to download so long as you own the game in question, or that you’re allowed to keep them for 24 hours or some other arbitrary amount of time. This is not quite true, as there are no actual laws that protect emulation, only a single case that protects a single aspect of emulation.

Video games are a relatively young medium, and any precedent is relatively young. Things aren’t fully settled here and may change in the future, like most law in the video game space.

The Law of Video Game Emulation as it is Now

There is no law protecting emulation. The only thing that establishes any sort of protection for emulation is a single case1 from the ninth circuit in 1999 called Sony Computer Entertainment, Inc. v. Connectix Corp.

The Legality of Video Game Emulators: Sony v. Connectix

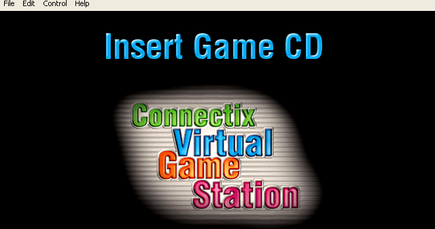

In Connectix, Sony was suing Connectix over their program the Virtual Game Station, a Macintosh application that would allow users to emulate PlayStation games. This would allow Mac users to play games for the PlayStation by inserting the discs that they had purchased. The program was created by reverse engineering the PlayStation BIOS, the Basic In/Out System that ran the PlayStation hardware. Sony viewed this software as a threat and took legal action against them. The court decided that Connectix had not violated Sony’s intellectual property rights as it was fair use to reverse engineer the PlayStation’s BIOS.

Code is protectable by copyright. Sony did (and still does) have protection over that. However, this protection does not extend to the functionality of that code. Reverse engineering a BIOS, or recreating it without incorporating the original code that is protected, would not infringe on a console maker’s rights. The purpose of copyright is not to grant a monopoly in this way, that’s what patents are for.

Any protection of emulators under Connectix is very narrow. It is legal to make an emulator. This is no doubt why even large companies like Apple feel comfortable allowing them on their app store.

You can even research how to do it by looking at the BIOS code, as it is granted less protection than other literary works. You can commercially release that emulator, and even make money, though you’ll be painting a bit of a target on your back if you do. The court didn’t take issue with this part of Connextix’s distribution of the Virtual Game Station.

You cannot use protected code from the console BIOS as part of the finished emulator. You can reverse engineer it to create an emulator that does the same thing, but not incorporate the original code into it. That code is still protected by copyright.

The takeaway here is that while a lot of people assert that Sony v. Connectix protects video game emulators within the United States, it’s only a very thin protection for a very specific type of reverse engineering when creating an emulator. The actual use of an emulator is a very different question.

As to the actual use of video game emulators by end users to play ROMs, that’s a bit hazy. Making and using an emulator is okay, but ROMs required to play any games are still protected works. You could download and play public domain ROMs that have no copyright protection on them, or homebrew games that are released as freeware.

However, that’s not what most people are using emulators for. Most people are using them to emulate commercial games. Those games are still protected by copyright, and downloading them is still piracy. There’s not an exception for games you own.

In theory, you could dump the ROM yourself from a copy of the game you own, but this hasn’t actually been tested in court. While the act of backing up or archiving software you own is protected under the U.S. Copyright Act, Nintendo’s stance on the matter is that this does not apply to video games as they contain various types of copyrighted works. It’s also in violation of their End User License Agreement. This hasn’t been tested in court yet, so the law isn’t clear here.

What’s the Legal Use of Video Game Emulators?

The creation of an emulator is legal, provided that it doesn’t contain code protected by copyright and is reverse-engineered. Downloading ROMs online is illegal, and if Nintendo’s theory is correct, then backing up copies of games that you legally purchased is also illegal. So where would that put emulation legally? What would be legal?

The strictly legal use of video game emulators would be creating an emulator and then using licensed ROMs with them. This is often easier than creating a new port. Companies like DotEmu have created a business out of this. They have released lots of games like classic NeoGeo games that are simply an emulator packaged with the ROMs as licensed by the copyright holders. This is legal under the current law, even without permission from the hardware manufacturer, presuming that the code is properly reverse-engineered.

That this would be legal even in Nintendo’s interpretation of the law is shown by how Nintendo themselves use emulation. Creating a video game emulator and packaging it with ROMs that they either own or are licensed from other companies is how their Nintendo Switch Online classic games or their previous virtual console services have operated.

Again, I’m not here to say what the law should be on this topic, only what the law is.

What Happened with Yuzu?

Now that we understand the legal history of video game emulators, let’s talk about Yuzu. The most interesting thing about it is that Nintendo’s legal case basically sidesteps Connectix and its protection of reverse engineering in favor of a new legal theory.

Yuzu is a Nintendo Switch emulator, developed by Tropic Haze LLC. In other words, it allows you to play Switch games without a Switch, and potentially without a legitimate copy of the game if you can get the ROM files. Tropic Haze was sued by Nintendo, largely provoked by the release of The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom (TOTK), a massive game that was playable on Yuzu on day one. Tropic Haze ended up paying $2.4 million to Nintendo in a settlement agreement.

In the aftermath of this lawsuit, Nintendo has been taking down Yuzu derivatives like Sudachi and Suyu, despite their questionable plans to avoid being sued, and has possibly been working with Discord to take down servers dedicated to their development. Github repositories for these derivatives have also been taken down due to DMCA claims.

What’s unique about this lawsuit is that Nintendo’s argument entirely avoids the decision in Connectix. Nintendo’s argument doesn’t center on Tropic Haze building an emulator, but on the fact that Yuzu is a tool to work around technological measures designed to protect Nintendo’s intellectual property.

17 U.S. Code § 1201 (2) (B) of the DMCA prohibits technologies that have “only limited commercially significant purpose or use other than to circumvent a technological measure that effectively controls access to a work.” This technological measure in this case, according to Nintendo, refers to Yuzu’s ability to break Nintendo’s encryption, which is designed to control access to a work, a game in this case, such that it can only be played on authorized hardware.

In this way, Nintendo’s argument avoids precedents like Connectix entirely. They don’t complain that Tropic Haze created an emulator, but that Yuzu breaks Nintendo’s encryption. This is a new legal theory in this space, though it’s similar to the one they made at the time of Dolphin’s Steam release. They don’t argue that Yuzu was reverse engineered, but that breaking this encryption violates this anti-circumvention provision of the DMCA.

Nintendo – or most other hardware manufacturers – haven’t historically taken many legal actions against video game emulators. Why now? Why this one? If a hardware manufacturer takes an emulator to court, there’s always a risk that video game emulators will get more legal protection than they currently have. This would be a problem for Nintendo and other hardware manufacturers. It’s a small risk, but it has potentially huge consequences for a company whose entire value rests in its intellectual property.

In this case, Nintendo was willing to take legal action. Yuzu set up a great case for them. Yuzu was highly publicized around TOTK’s release, and they did things like providing instructions and links to illegitimate ways to get Switch encryption keys as part of its quick start guide while also being hesitant to host these files themselves, indicating that they knew it was a problem. It also was a case where damages would be calculable since Tears of the Kingdom’s release led to an increase in Tropic Haze’s Patreon revenue as well as an increase in users playing the game on Yuzu. Given these facts, Nintendo was likely to pursue litigation if Yuzu hadn’t settled.

Conclusion

To be clear, this is the legal standing of emulation, not the moral one. That’s a different topic, touching on issues of accessibility and preservation of older games that aren’t available anymore. Emulation doesn’t have to be just about piracy.

While emulating old games that aren’t available to purchase from the copyright holder seems to be harmless, that’s not how the law views it. Under the current copyright laws, a copyright holder has the right to exclude others from using their work, even if they’re not currently making it available to players.

Much like modding, copyright holders get a large amount of control over how their IP is used. The law as it is gives them the right not to exploit their own work, which has led to many beloved games that simply aren’t available to purchase or play outside of emulation.

There are great benefits to emulation, but it’s on legally shaky grounds. It’s important to understand that emulation is not as protected by the law as people tend to think.

If emulation is going to survive as it currently is, the creators of video game emulators need to take care not to create conflicts with large companies whose interests might be harmed where they don’t have to. Yuzu’s emulation of a current generation console to play big games on day one after release is one such example of this, it provoked Nintendo where they didn’t have to. The law is somewhat unclear here, but all it takes is one company like Nintendo deciding they want it to be made more concrete.

- A lot of people also cite Sony Computer Entertainmment America v. Bleem LLC. This is mistaken in most contexts that it is used. Bleem is a case about emulators that doesn’t touch on the legality of emulators, only questions of copyright infringement over Bleem’s use of screenshots from PlayStation games to compare their software against actual Playstation hardware, which was found to be fair use. The legality of emulation is only touched on in that it cites Sony v. Connectix on the question and then it quickly moves on. ↩︎

Leave a Reply