Games are a unique industry in that they are art, entertainment, and also business. While some idealists may think of the business as totally separate from the art and entertainment – make a good game and people will pay money to play it – the reality is that the business side of things has far-reaching implications. We naively believe that it doesn’t, but monetization affects game design.

How a game makes money from customers fundamentally affects how the game is designed, and historic shifts in how games have been distributed have led to shifts in game design principles.

In this article, we’ll take a look at three of these changes in how games have been distributed historically and how these changes have affected how games are designed and played.

From the Arcade to Home – Changes in Game Length

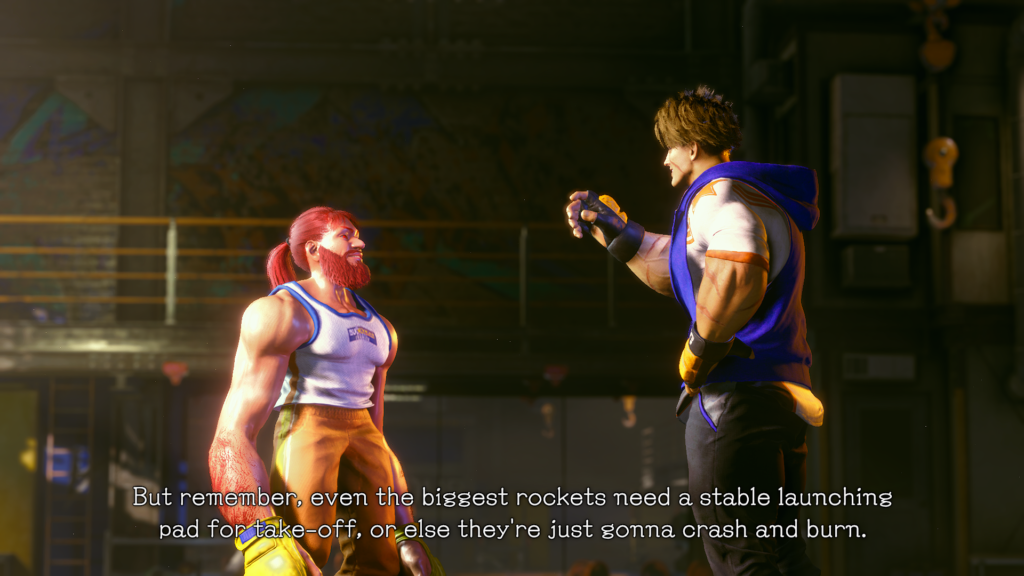

While I didn’t grow up going to the arcade, they still hold a special place in my heart as a player and fan of fighting games like Street Fighter. While arcades have been around for a lot longer, the modern idea of the arcade dates back to the 70’s. Video games as we know them were popularized in arcades. Even when home consoles were readily available, the arcade would be where you could see graphics and gameplay that just weren’t possible at home. Now, arcades have largely lost their place in our culture in favor of home consoles and largely focus on games that prioritize dispensing tickets over great and cutting-edge gameplay. There are places such as this one in Pakistan focusing on Tekken that still exist as a social place to gather and play games together.

The transition from arcades to home consoles has had implications for game designers. Arcades made money one quarter at a time. You want to play a game? Put a quarter in and you can play until you run out of lives, then it’ll be another quarter to continue or start over. Designers had to give enough gameplay that a player had a good experience and wanted to try again, but not so much that a player would stay on for a long time and thus limit how much money the game could take in.

Games on home consoles work a bit differently. You purchase a game for a sum of money, then you can play as much as you want. The money has usually already been exchanged when the game starts. This led to two major notable changes in game design.

The first is that games no longer had to restrict your time, leading to some discussion as to whether or not having lives is an outdated design choice that’s unneeded in the post-arcade era since players can just keep playing without putting in a new quarter. Lives don’t make as much sense when you can keep playing without having to put in another quarter.

The second is that games could be longer. While an arcade game was meant to be played in sessions only lasting a few minutes, home consoles allowed for much larger adventures that could take much longer to complete, and often would have to in order to make the purchase feel worthwhile. Longer-form adventures like those found in Zelda, Metroid, or any other longer game became possible because of the shift from arcades to home consoles. Game design shifted as game sessions became longer, and the amount of content in a game had to be increased as a result.

Online Games and Free to Play

In my mind, the proliferation of free-to-play games and online games go hand in hand. It doesn’t make much sense to base your game’s monetization on collecting or paying for new characters or skins if it’s primarily a single player offline game. On top of that, multiplayer games benefit the most from having a lower monetary barrier to entry inherent to free-to-play, allowing for the much bigger playerbase required by a multiplayer game where larger numbers of players are required for good matchmaking.

The decision to make a game free-to-play brings with it some design considerations. It’s not enough to decide that a game should be free to play towards the end of its development – monetization is something that has to be considered from a very early stage and throughout the development process.

This shift towards free-to-play games, particularly for larger multiplayer games that require massive player bases like battle royales or most other types of competitive games, has led to a lot of different monetization methods being created in the last several years, some far more predatory than others. Some games like League of Legends opt to make the game itself free and then sell skins and other cosmetics to players. Other games like Fortnite will often tie these cosmetics to a Battle Pass, where players have the option to purchase the pass to then unlock its content over a set period of time. Some will sell loot boxes that may or may not contain the item that you’re after. On the more sinister side, there are some games that allow players to purchase more powerful characters or weapons or otherwise pay for advantages against other players, often called “pay to win” by players.

Whatever route a free-to-play game takes, it’s something that has to be considered very early on and isn’t always possible or wise for every game or developer to pull off. The opportunity for a larger player base due to the lowered cost of entry is tempting, but free-to-play games tend to only work well in very large volumes, and require careful design decisions throughout the process.

Game Pass and Other Premium Subscriptions

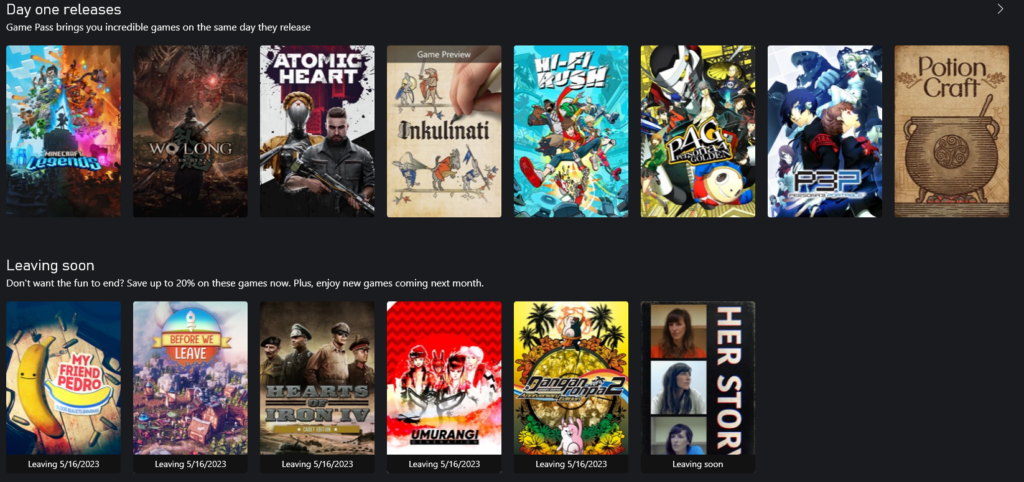

Xbox Game Pass and similar services like Apple Arcade are relatively new, so their impact on actual game design hasn’t really been fully seen yet, if any. As such, we’ll have to speculate on how premium subscription-based services could affect game design.

Game Pass and similar services are like Netflix in that players can pay a set fee to then play any games they want on the service during their subscription period. Xbox has been pushing this service hard, which makes a lot of sense given that the games can be played in the cloud even if players don’t have an Xbox.

How do games offered on Game Pass make money then? Phil Spencer has addressed this question in an interview, and the answer is that it varies from game to game. Some developers get a set sum of money in exchange for their game being offered on Game Pass for a set period of time, others may be based on usage and monetization. It all depends on what the developer works out with Microsoft.

Like any decision affecting monetization, the decision to make a game available on Game Pass carries implications for the design of the game itself. Shorter games like Hi-Fi Rush can be shadow-dropped on Game Pass the same day they are announced and do very well without needing to worry about making back their budget since the deal with Game Pass ensures some automatic revenue.

A game on Game Pass can still make money in other ways as well. A game could continue to sell other DLC or expansions, with the base game offered on Game Pass. A rise in the popularity of such services could lead to an increase in such practices and design decisions, and a higher reliance of developers on sales after the initial purchase. Still, it would allow players to play the game as part of their subscription, then purchase additional content to support the game if desired, and it would be just fine if done well. This would allow very successful games to make more than they otherwise would, but additional content beyond the initial purchase would be something that designers would have to consider.

Still, if Microsoft does decide that usage and playtime is the better metric for how much money a game should make, this could have greater implications for how a game is designed. This is already how Netflix works, with the first several days of airing acting as a metric for whether future seasons will be ordered. If Game Pass shifted its model with developers to be more focused on playtime for payment, it could very quickly lead to developers padding out their games with content that isn’t as high quality or requiring grinding or other repetitive activity to increase playtime.

Of course, there is also the argument to consider that having your game on Game Pass or other subscription services – especially immedately at launch – can devalue your game as well as games as a whole and cause customers to be more likely to spend money beyond the purchase of their subscription.

Still, this is mostly speculation. Premium subscription services haven’t been around long enough to really impact game design, so it has mostly remained a decision for how the business is run. Right now, while Game Pass tends to give developers a shot of money before release, not unlike a publishing agreement, there is some debate as to whether or not it hurts sales long-term or actually leads to increased game sales.

Game Design and Business Go Hand in Hand

There are many more ways that the business and distribution side of video games affects their design. It’s worth considering at every step of the process how your game will support that business, and how the business will affect your design. A game’s design often needs to change to accommodate how your game is distributed and monetized, and industry trends as technology evolves often leads to great changes in how games are played.

Have your own questions? Schedule a free consultation below.

Leave a Reply